There’s no question that running is good for your brain. From boosting memory and focus to reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression, the cognitive perks of exercise have been well-documented. In fact, the CDC lists physical activity as a key factor in supporting problem solving, emotional stability, and learning. And a research review in Comparative Physiology even suggests that regular exercise, combined with a healthy diet, may help stave off neurological and cognitive disorders.

But a new study in Nature Metabolism adds an intriguing twist: marathon running may cause a short-term dip in a vital brain component related to coordination and sensory regulation.

Sound alarming? Not so fast.

In this study, researchers from the University of the Basque Country in Spain performed detailed MRI scans on 10 runners (ages 45 to 73) before and after they completed a marathon. What they found was a significant decrease in myelin water fraction—a measure of myelin content—in areas of the brain responsible for motor function, emotion, and sensory processing.

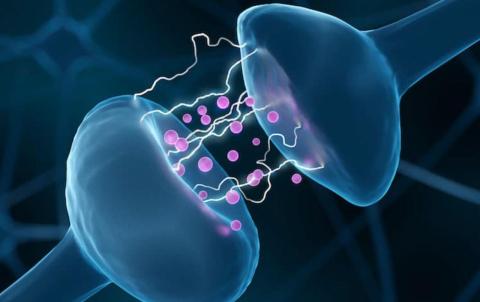

Myelin is the fatty sheath that wraps around nerves, helping electrical signals travel smoothly and quickly. Less myelin water fraction could indicate temporary disruption in communication between neurons, which might affect balance, coordination, or emotional regulation—at least in the short term.

But here’s the key: the researchers believe this process is likely part of a normal, adaptive response. “We think it’s a transient phenomenon that reflects neuroplasticity,” said co-author Carlos Matute, Ph.D. In other words, just like your muscles break down slightly during a marathon and rebuild stronger afterward, your brain may be undergoing its own form of recovery and strengthening.

In fact, follow-up scans showed signs of recovery: two weeks after the marathon, two runners showed signs of rebound myelin levels, and at the two-month mark, six participants appeared to have fully recovered.

It’s worth noting that the study had a small sample size and didn’t include a control group. So while the findings are interesting, they’re not yet definitive. More research is needed to confirm the patterns and understand how widespread or impactful these temporary changes might be.

Still, this study opens the door to an exciting new conversation about how endurance training affects the brain—not just in terms of cognitive performance, but structural adaptation. And for now, it doesn’t change what we already know: regular exercise, including marathon training, remains one of the most effective tools for protecting and enhancing brain health.

So keep lacing up. Your brain is going on the journey with you—and it might just come out stronger on the other side.

Discover More Content